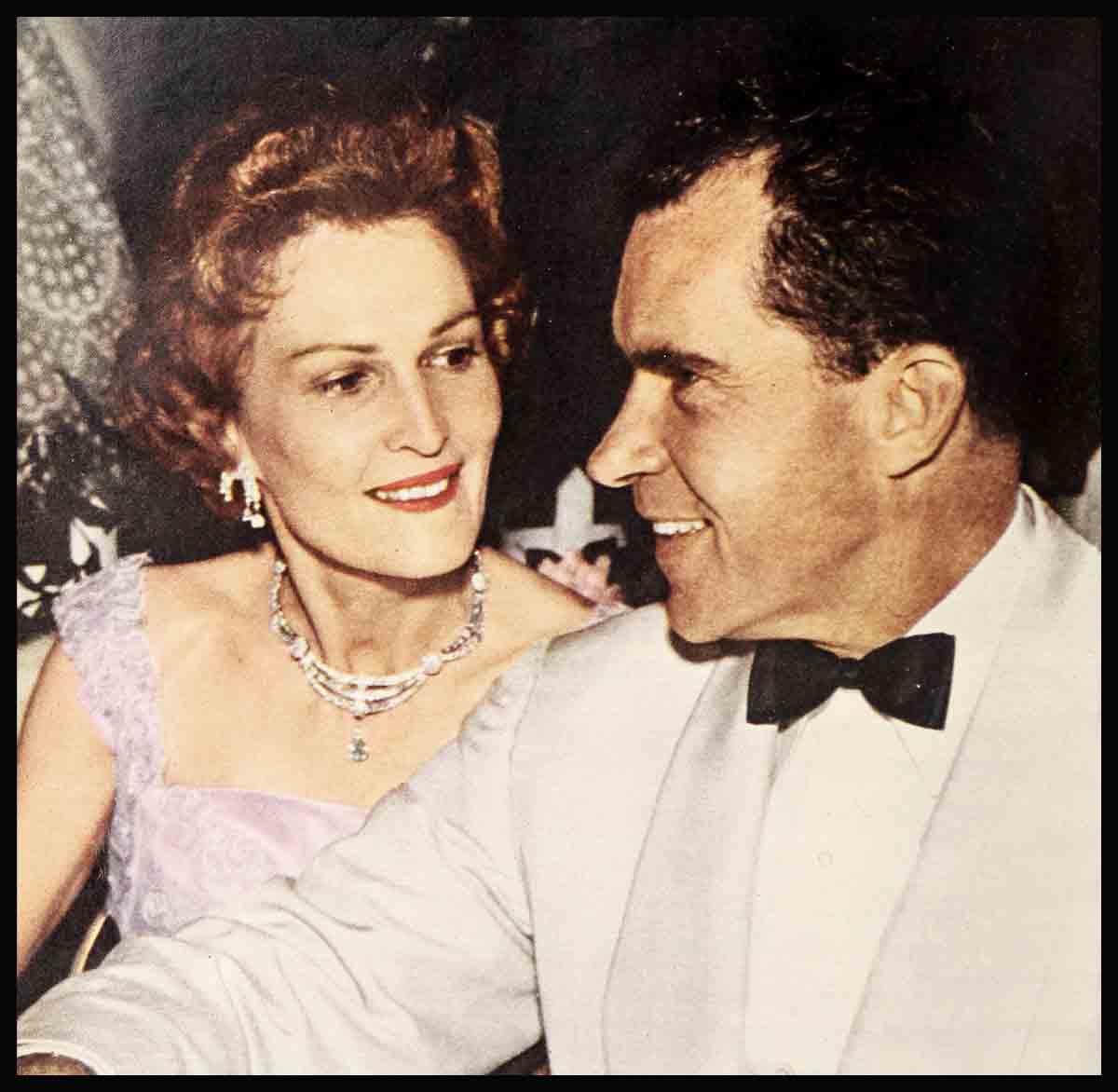

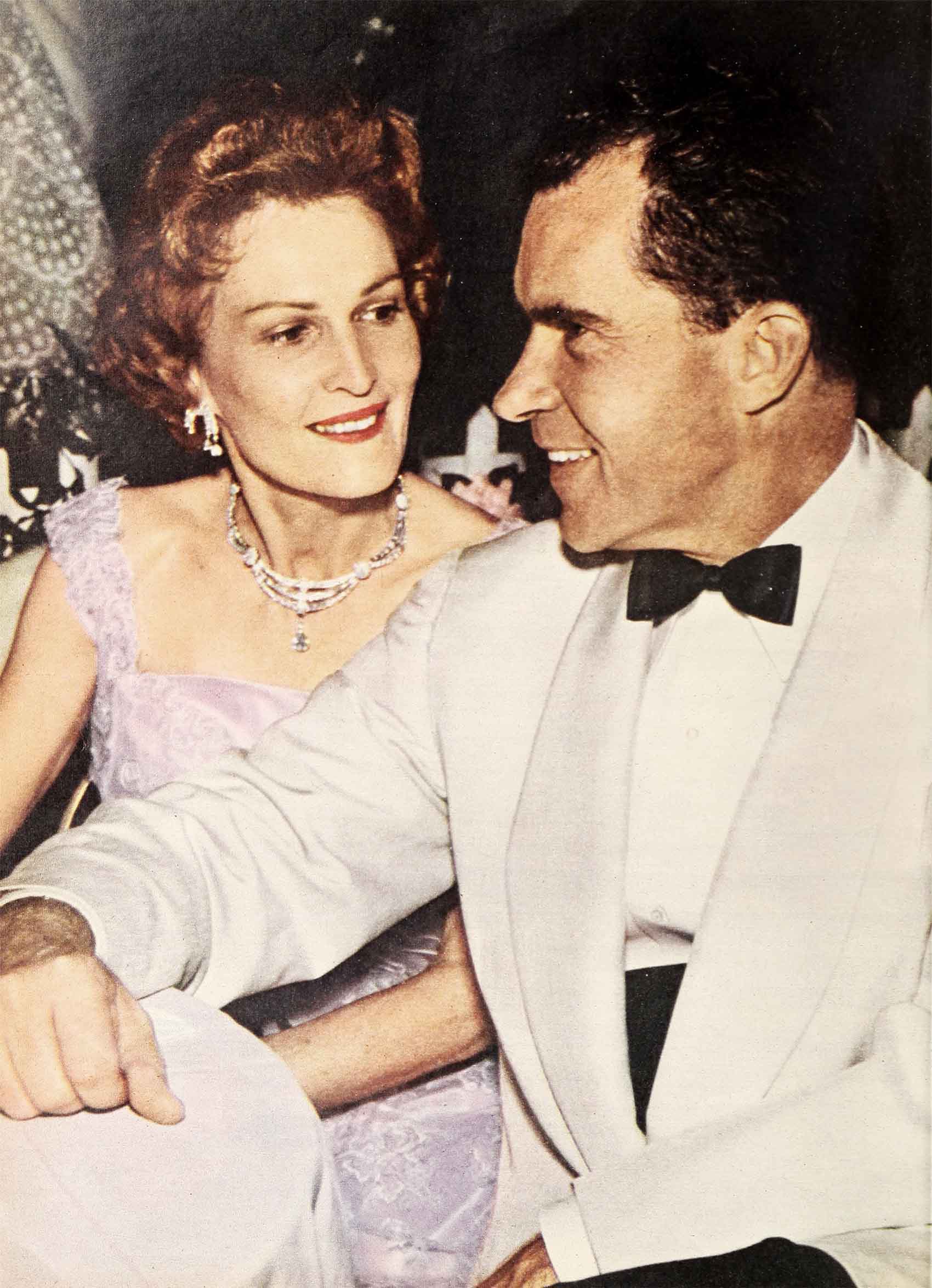

The Love Story Of Pat And Richard Nixon

Pat Ryan was seventeen, the daughter of a Nevada miner, when she went to Hollywood. She was full of hope and dreams. She stayed for a month. It was a disillusioning experience. She got one job, as a walk-on in a picture called Becky Sharp. She got twenty-five dollars for the job. But after that, there were no more jobs to be had. And one day, after a lifetime of dreaming, she decided to give up her “career” and become what she knew both her parents had always really wanted her to become. She would be a teacher.

She worked her way through college, as a librarian, a countergirl, a bookkeeper, a typist, an X-ray technician. And when, finally, she graduated, she got a job as commercial subjects teacher in the California town of Whittier, just outside Los Angeles. She became, quickly, this thin and pretty blonde, one of the most popular teachers at the school, and one of the most popular young ladies in town.

She dated lots, those who knew her recall. It seemed for sure at one time that she would marry a certain very good-looking merchant in town.

But then she met the young lawyer, and then her heart began to shift affections.

Not rapidly; not at all rapidly. Local gossip has it that while the lawyer was head over heels in love with Pat, she herself played it slowly, coyly, even teasingly at first.

“There’s a story,” she said recently, “‘that my husband, before we were married, would drive me to dates with other young men in Los Angeles and then would wait around to drive me home . . . That’s true,” she laughed, “but I think it’s awful mean to report it.”

One night, however, after about six months of indecisive going-together, Pat’s pet collie died suddenly and when the young lawyer phoned to ask if he might take her out, she wept into the phone: “No, no, I don’t want to see anybody ever again!”

Later that night, the lawyer showed up at her door.

He handed Pat a package.

“If I were rich,” he said, “I’d have bought you another collie . . . But since I only had six dollars on me, this was the best I could do.”

Pat opened the package.

Inside was a small woodcut. of a dog, a collie.

With it was a note which read: “May I have the pleasure of being your new friend?”

Pat knew now that this man, “this sweet, wonderful fellow,” was the man for her.

As only a woman can, she got him to propose officially to her later that night. And when he did she said, breathlessly, as if surprised and delighted, “Why yes!”

There was only one slight hitch. the lawyer told her then. “My mother’s a little worried about your having a ‘Hollywood’ background. It won’t make any difference for us either way. But I’d like you to meet her and show her what you’re really like . . . Okay?” he asked.

“Oh boy,” said Pat.

HANNAH NIXON SAT ALONE with Pat in the Nixon parlor that next afternoon. They sat next to one another on a small couch. On a table in front of them were two cups of tea and an aging scrapbook.

“I know my Richard must be in love with you,” said Mrs. Nixon, beginning, her voice very matter-of-fact, her eyes never once off Pat. “In the past whenever he came back from other dates he talked not of romance but about such things as what might have happened to the world if Persia had conquered the Greeks, or what might have happened if Plato had never lived . . . But after his dates with you, Miss Ryan, well, he talked only of you.”

There was something about the way she’d said you that caused Pat to move a little, uncomfortably, in her seat.

“Now,” Mrs. Nixon went on, “since you’re going to marry Richard, I guess there’s a lot you’ll want to know about him . . . First of all, let’s see; yes, there’s food to be discussed. Most foods don’t interest Richard, you know. But there are two things he likes. One is cherry pie. One is rump roast beef . . . Do you know how to prepare them, Miss Ryan? Pie and rump roast?”

“Yes,” said Pat, “I do.”

“Hmmmm,” said Mrs. Nixon. “Now—about clothes. I’m afraid you’re going to have to do a lot of Richard’s shopping. If his brother Donald needs a new suit, Richard will buy it. But if Richard needs one, he’ll get me to buy it, or do without it . . . That’s a job you’ll be having to take over, Miss Ryan. Will you mind that?”

“Oh no, not at all,” said Pat.

“You’ll find, too,” Mrs. Nixon went on, “that Richard is a hard worker. But work for him has not been connected with making money. I have never heard him express a desire to be a financial success . . . Does that matter to you, Miss Ryan, if your husband is not a financial success?”

“It would have a few years ago, when I was younger, sillier,” said Pat. “It doesn’t any more.”

Mrs. Nixon smiled, a tiny bit.

Then she said, “I hear you’re an orphan.”

“Yes,” said Pat.

“I’m sorry,” said Mrs. Nixon. mother passed on first?”

“Yes,” said Pat. “When I was a young girl. Her heart gave way.”

“And your father?”

“He died just as I was finishing up high school. He had silicosis. I tried to nurse him as well as I could. But—”

“BUT WHILE THEY LIVED,” Pat said, “they were very happy. I’m glad for that. I thank God for that.”

Again Mrs. Nixon smiled, a little.

Then she reached forward and picked up the scrapbook in front of her. She turned a few pages.

“This,” she said then, pointing to a photograph, “is Richard, right after birth.”

Pat grinned.

“He was adorable,” she said.

“A very well-formed baby, I thought,” said Mrs. Nixon. “And this,” she said then, “is Richard at nine months, the time he said his first word. It was ‘bird.’ He was referring to a white horse of ours named Bird.”

“Dick’s told me about him,” said Pat.

“And this,’ she said then, “is Richard at ten, the time he said to us he wanted to be a lawyer when he grew up. We thought he would be a musician, he had such a good ear on the piano: or maybe even a preacher, he could talk so well. But he said ‘lawyer’ one day, and I could see he had a sense of justice about him.

“You see,” she said, “we had a store at the time and we found that one of the customers had been shoplifting. Everybody thought that I should turn the woman over to the police. But Richard said ‘Don’t do it, Mother. If they arrest that woman, it will ruin the lives of her two children.’ I followed Richard’s advice. And I’ve never been sorry I did.”

When she was through talking, she saw Pat kiss her own fingers and then bring them down, softly, onto the photograph.

“What made you do that?” Mrs. Nixon asked.

“I don’t know,” Pat shrugged. “I guess it’s that up till now I loved the man . . . But now I love the boy that he used to be, too.”

“Well—” said Hannah Nixon.

And then, for the first time that afternoon, she smiled, really smiled, a warm and deep smile.

“Well—” she said again, “that was a very nice thing for you to say.

“And I’m glad, Pat, very glad that you’re the girl who’s going to marry my son.”

Pat and Dick Nixon were married early in 1940, in a Quaker church in Riverside, California.

When—soon after the United States entered World War Il—Dick joined the Navy, Pat quit her schoolteaching job and followed her husband, happily, in her usual happy-go-lucky way, from billet to billet.

They lived in Washington for a while, then Iowa, then Philadelphia. When Dick was sent to the Pacific, Pat took an apartment in San Francisco and a job there, as a stenographer.

Finally, towards the war’s end, Dick came back to the States and he and Pat took off together for Baltimore and his last Navy assignment.

In Baltimore, after a while, Pat became pregnant.

And in Baltimore, too, after a while, Dick received the telegram that was to change the course of their entire lives.

The telegram read:

ARE YOU INTERESTED IN RUNNING FOR CONGRESSIONAL SEAT SOLIDLY HELD BY DEMOCRAT VOORHIS?

(SIGNED) THE COMMITTEE OF ONE HUNDRED.

“What do you think?” Dick asked Pat after they’d read it.

“I think it’s great,” she said. “It’s a real big honor. You should be mighty proud.”

“I probably wouldn’t win,” Dick said, “even if I do tell them yes.”

“So what?” said Pat. “It’ll probably get is back to Whittier, quicker than we’d planned … And if you lose, we’ll get ourselves a little house there and we’ll have our baby there, you’ll open up a law office again, and—and meanwhile, Dick,” she said, “a political campaign. I bet that’ll be an awful lot of fun! . . .”

It was night, in California, several months later.

DICK HAD WON THE NOMINATION a few days earlier. The campaign had officially begun.

But now, this night, Pat lay in the hospital room, about to be taken to the delivery room, where she would give birth to her first child.

“I want my husband,” she said, groggily, to the nurse who stood alongside her. “Where’s my husband?”

“I phoned him, dear,” the nurse told her. “Now don’t you worry. He’ll be here. Soon. . .”

Dick rushed into the room a few minutes later.

“Darling,” he said, taking Pat’s hand, “I just got the call. I was at the Elks’, in the middle of a speech. I wanted to get here. To hold your hand . . . To give you this.”

He bent and kissed her.

“Dick,” Pat asked then, “are you going to stay—while I’m inside?”

He didn’t answer at first.

“Dick?” she asked.

“I shouldn’t, honey,” should get back.”

She closed her eyes.

“Pat,” he said. “I’ve started this thing. For better or for worse. There are more than four hundred people back there, in that hall, waiting to hear what I’ve got to tell them. If I’m going to do this thing at all, Pat, I’m—”

He stopped. And, after a moment, Pat could hear a chair being pulled up next to her bed.

She opened her eyes.

She saw that Dick was seated next to her.

“I’m sorry, honey,” she heard him say. “I’ll stay. Of course I’ll stay here with you. Nothing’s more important to me than you, Pat . . . I don’t know what got into me just now.”

She looked up at him. She forced a smile as best she could. “No, Dick,” she said. “I’m the one who’s sorry. If you’ve got to go back, you’ve got to.

“Please, Dick,” she said, “go back to your speech.

“I understand,” she said.

“Believe me, Dick, I do understand.”

And as she said that, she continued to force her smile; while, under the bedsheets, she clenched her fists, tightly, partly because of the pain inside her, and partly because of another pain . . . a pain she knew would never leave her and over which, she knew, neither she nor her husband would ever again have any control. . . .

Dick Nixon won the ’46 election. And he and Pat and Tricia (the first of two daughters) moved to Washington.

For the next six years, first as a Congressman’s wife, then as a Senator’s, Pat learned fast that a perfect politician’s wife must be silent, serene, well-controlled and always smiling.

BACK IN THE EARLY DAYS, however, Pat’s only concern was her usefulness towards her husband. Was what she was doing the right thing for Dick? He seemed unusually happy here in Washington. His star was rising. Was she right in there, doing a good job for Dick, helping him in the hundred little wavs that she could?

Finally, one night in July of 1952, it appeared to Pat Nixon that yes, she had done a good job.

Dick stood on a platform, waving his arms, smiling at the thousands of convention delegates who had just nominated him for the next Vice-Presidency of the United States of America.

And next to him Pat stood.

Yes, it seemed to Pat, that night—everything had been worth it.

Because everything, everything in Dick’s life was just perfect now. . . .

But then, another night, shortly after, things began to change. A few hours earlier, a story had broken in the newspapers and on TV. Dick Nixon had been accused of illegally accepting funds and gifts (quite a bit of money, it was reported, as well as a dog named Checkers) from several wealthy Californians. Within these few hours since the story had appeared, public reaction had become nearly hysterical. There had been cries from the Democrats, and from many Republicans, too, for General Eisenhower to throw Dick Nixon off his ticket.

PAT HAD READ THE STORIES, heard the accusations.

She’d tried to rub them from her mind.

She sat there now, this night, in her living room, with her mother-in-law, silently, still trying.

When, suddenly, she heard the cars pull up the driveway—first one, then another, then a third.

A moment later, the front doorbell rang.

Pat didn’t move.

“Aren’t you going to answer?” asked Dick’s mother.

“No,” said Pat. “Not tonight, I’m not . . . Dick’s inside, writing his talk. The children are asleep . . . I’m not going to have anybody disturbed tonight.”

But then, after a while, when it seemed as if the bell would never stop ringing, Pat rose, and headed for the front door.

She opened it, quickly, nervously.

“Mrs. Nixon?” a reporter called.

“Yes?” she asked.

A flashbulb popped.

She blinked.

“Yes?” she asked again.

“We’d like some shots of your husband . . . and a statement.”

“I’m sorry,” she said. “He’s in his office. He has a speech to give on television tomorrow. He’s busy.”

“How about the dog then? Can we get a picture of him?”

“I’m sorry, but—”

“Aw, c’mon, Mrs. Nixon. The whole world wants to see this pooch.”

“What do you say, Mrs. Nixon.”

“C’mon, Mrs. Nixon.”

“It’s our job, lady. We’ve got to get that picture.”

Pat found herself nodding. “All right,” she said. “All right . . . but please, be quiet as you can. The girls are sleeping. I don’t want to wake them.”

“Sure thing, ma’am.”

“Don’t worry, Mrs. Nixon.”

She opened the door wider.

The newspaper people rushed past her.

“Please now—” she started to say.

But they were already far past her, on their way up the stairs. They thumped up the stairs. And they shouted to one another. They acted like kids on a lark. Pat watched them, unbelievingly.

“Mama,” she heard a voice call out to her, suddenly.

She looked up, to the top of the stairs.

A door was open there. In the doorway stood her two little girls, in their pajamas, their faces covered with fear.

“Mama,” asked Tricia, the older one, “is anything wrong?”

Pat stood there, staring at her girls.

“Mama!”

“I don’t know, Tricia,” she said, finally.

“Hey,” one of the reporters called out to the girls. “Is this the door to the dog’s room?”

“Yes,” the girl said.

The men barged into the room.

“Mama,” Julie, the younger daughter. called now. “what do they want with Checkers? What do they want with my doggie?”

“Nothing, sweetheart,” Pat said. “They’re just going to take his picture. That’s all . . . Go back to your room now. Both of you. Go back to bed now.”

She watched the two girls as they stepped back and closed their door. And then she walked back into the living room and over to a window.

“What’s wrong, child?” her mother-in-law asked.

“I CAN’T TAKE IT ANY MORE,” Pat said, staring out of the window.

“I know,” her mother-in-law started to say. “It’s hard on you all sometimes. But—”

“I just can’t take it any more,” Pat went on. “It’s too hard on the girls, too hard on me. And now, Dick—it’s too hard on him.”

“What are you going to do?” her mother-in-law asked.

“I’m going in to Dick, and talk to him.” Pat said.

“What are you going to talk about?”

“I’m going to ask him to quit, to quit,” Pat said. “I’m going to tell him that I want to go home. With him and our daughters. Home where we belong. Not here. Not here, where they scandalize us, and hurt us so much. Not here—”

She turned from the window and she faced her mother-in-law.

“You’re his wife, Pat,” the woman said “You know best.”

“Yes,” Pat said.

She took a deep breath.

And then she began to walk towards her husband’s office.

Dick looked up at her. He’d been working hard and long and his eyes were tired-looking, very tired-looking.

“Yes, Pat?”

His voice was weary.

She stood there, in the doorway. She looked at him for a long time.

And as she did, she saw that there were tears in his eyes.

She had never seen him cry before.

Not once, since that first time they’d met.

“Yes, Pat?” he asked again.

In that moment that followed, she threw aside everything she had meant to say.

“I only wanted to see how you were, Dick,” she said, instead. “—And . . . to tell you . . . please . . . to go on.”

Then she walked over to where he sat.

And she put her arms around him.

“Go on,” she said, again.

Then she, too, began to cry. . . .

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1960

No Comments